PEBBLE BEACH, Calif. – With all the pomp and circumstance of the U.S. Open’s long and storied history at Pebble Beach, as well as the course’s glorious 100th anniversary this year, it’s easy to forget that the PGA Championship also was contested by the shores of Carmel Bay, and that it gave us as zany, wild and dramatic a major as it has at many of its U.S. Opens.

First came the ridiculous: The PGA decided to test clubs at a major championship for the first time in 30 years. The issue was the width of the Ping iron’s grooves; we’re talking about the thickness of a dollar bill, a few thousandths of an inch. But as we all know, when hitting a 1.62 ounce ball that’s 1.68 inches in diameter towards a four-and-a-quarter in cup, those thousandths of an inch mean a few feet of backspin and control. At the highest level, it’s quite an advantage.

It led to madcap scenes. Just one hour before tee time on Thursday, Tom Watson found out that his entire set of irons was non-conforming. In 1977, Watson was the game’s best player. He’d won five times that season, including the Masters and British Open, seizing both in swashbuckling mano-a-mano duels with no less a personage than Jack Nicklaus. Watson also tied for seventh at the U.S. Open at Southern Hills in Oklahoma, and he had already won the Bing Crosby Pro-Am at Pebble Beach earlier that year, in January. And now here he was minutes before the season’s last major – the only major he never won in his career as it turned out – and he’s running around the practice putting green like a demented Hobbit.

“Who’s got extra clubs? Who’s got clubs? I’ll take anything. Anything!” he panted desperately.

Finally, he corralled a set of MacGregors from Roger Maltbie. How ironic. He was now playing the same clubs that Jack Nicklaus used against him, and which he beat back both times.

But back then, Watson could play with a rake and an Easter egg and still contend, and with just eight practice shots, he shot an opening 4-under 68. For the record, Ray Floyd’s irons were also non-conforming. He lost his whole set, Hale Irwin lost two irons, and Tom Weiskopf lost a wedge. Jack Nicklaus’s clubs were fine.

(In 1948 at Riviera when they went after MacGregor clubs, anyone playing them had to have the irons filed down. That included Hogan, Byron Nelson and Jimmy Demeret. Nevertheless, Hogan fired an 8-under 276 aggregate, breaking the all-time Open scoring record by a whopping five shots. Grooves? What grooves?)

So were Gene Littler’s, and the diminutive, but smooth and sweet swinging old man quickly stole the headlines from the young Turks that had formerly relegated him to the role of bit player or extra on the Tour. But Littler was a sly old fox. He’d rope-a-dope people into sleeping on him with his aw-shucks drawl and hayseed quotes.

“The winner is usually the one who scrapes it around the goodest,” he once said in what is definitely not the King’s English, but was close enough for jazz in his home town of San Diego.

Littler burst on to the scene winning the 1953 U.S. Amateur at Oklahoma City Golf & Country Club, a Perry Maxwell and Alister Mackenzie masterpiece. Then his closing 68 at Oakland Hills won him the 1961 U.S. Open. Littler also had particular success and memorable highlights at Pebble Beach. He captured the Bing Crosby National Pro-Am in 1975, becoming the only player to win the event as both a professional and an amateur. He took home the team competition as a 23-year-old amateur in 1954, and also was a two-time medalist of the California State Amateur at Pebble Beach, winning the 1953 title.

Feeling right at home, Littler brought the sublimity to the tournament; he played magnificent golf for three-and-a-half days. He held the outright lead after Round 1 with an opening 5-under 67, one ahead of Tom Watson, two ahead of Jack Nicklaus and Lanny Wadkins, and three ahead of Johnny Miller. Littler followed with a 3-under 69 on Friday to take a two-shot lead over Jerry McGee. Nicklaus and Wadkins were now four back. A third-round 70 got Littler to 10 under, four ahead of Nicklaus and six clear of Watson and Wadkins, and he even increased the lead to five as he made the turn on Sunday.

But then the back nine at Pebble Beach did what the back nine at Pebble Beach does so often: turn golfer’s carriages into pumpkins.

Littler bogeyed 10 when he couldn’t save par from the greenside bunker. Then he three-putted 12 for a bogey. He bogeyed the 13th after a squirrely second shot, a mediocre chip and a fanned putt. He bogeyed 14 after hitting into a fairway bunker. And he bogeyed the 15th with another unforced error, a short iron that ended up in a bunker.

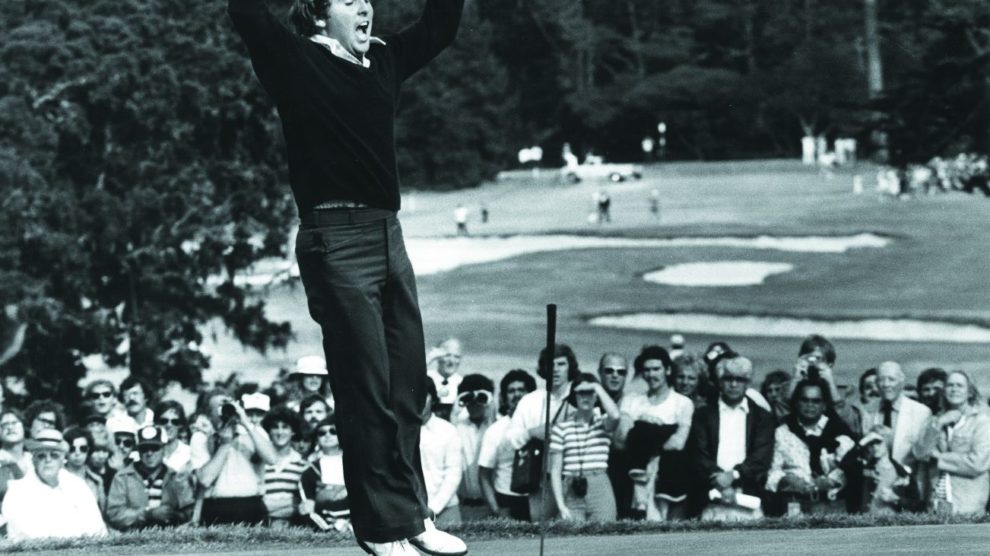

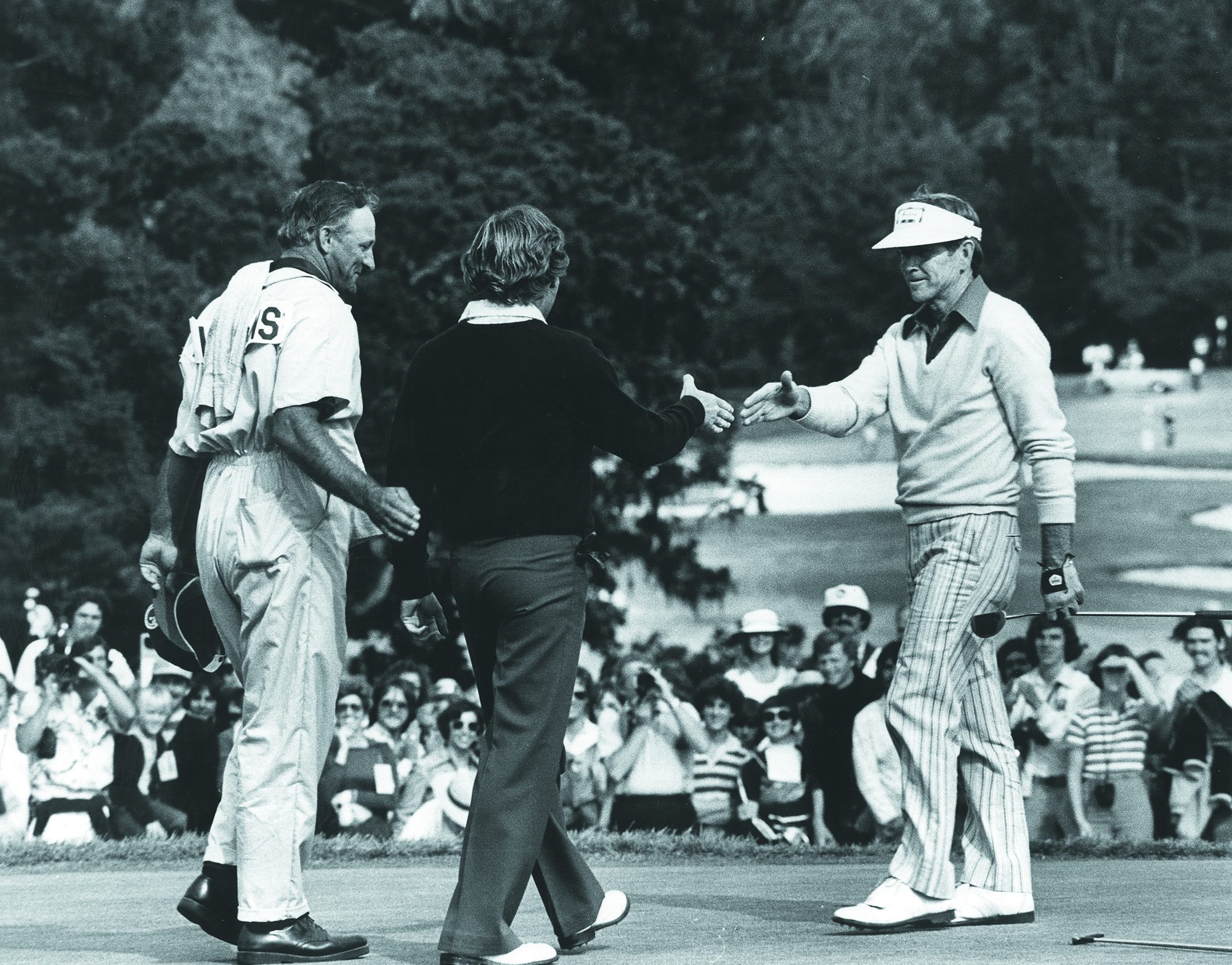

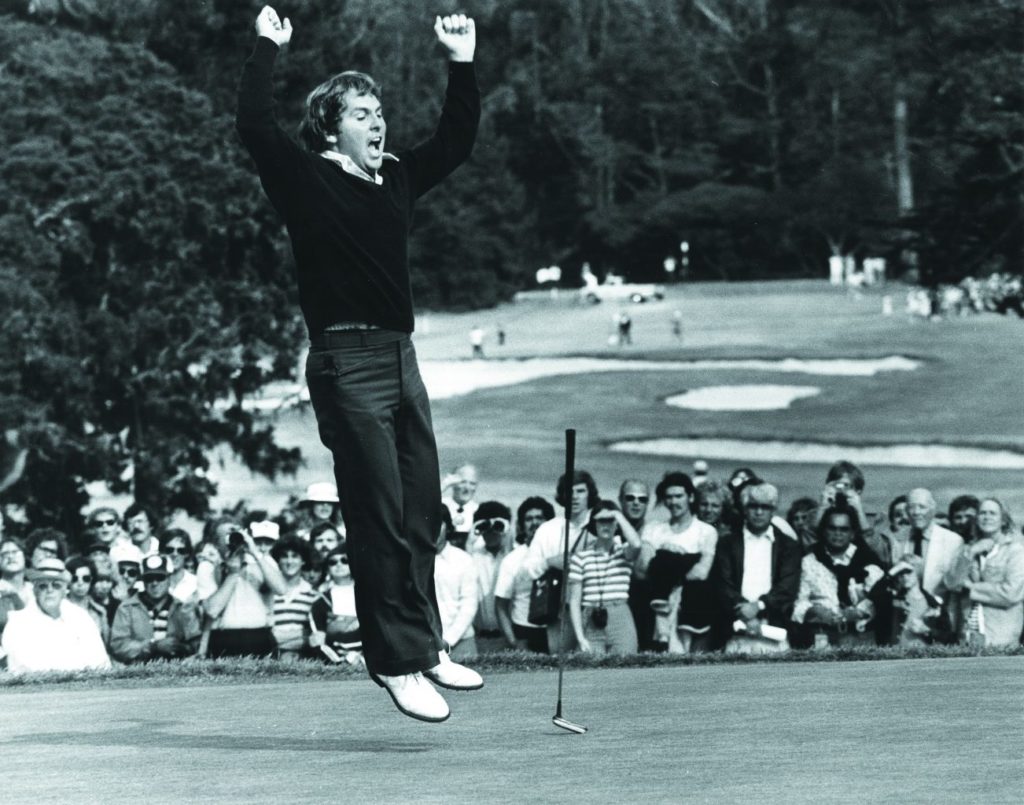

Meanwhile, fresh off a birdie on 18, Lanny Wadkins watched Littler miss a short putt that would have won him the Wanamaker trophy and, told he had to head out right away, he grabbed Dan Jenkins’s beer out of his hand shouting “Gimme that.” He chugged half, wiped his mouth on his sleeve, shouted, “That ought to do it,” and dripping suds on the locker room floor, he high-tailed it to the first tee for the first sudden-death playoff in major championship history, which he won with a par on the third extra hole.

The final twist had arrived. First Wadkins made up six shots in 6 holes. Then he saved par from deep rough on one to extend the playoff. Then he lasered in the four-footer that gave him the only major victory of his illustrious career. It was also the last time Gene the Machine contended at a major, ending a an era of grace and excellence.