FAIRFAX, Calif. – Call it the Machu Picchu of golf.

From far below, in the hippie town of Fairfax, one can look a thousand feet sheer up the cliff-side to the shallow, mountaintop bowl where the verdant fairways of Alister Mackenzie and Robert Hunter’s Meadow Club lie, serenely etched between fescue-clad rocky slopes.

Indeed, the first time I saw Meadow Club, it radiated an almost holy glow. A glorious sun blazed from a cloudless sky, and a golden crown of glory shone upon her every fairway, while somber Mount Tamilaus looked over her in stony silence, as he had for close to a century.

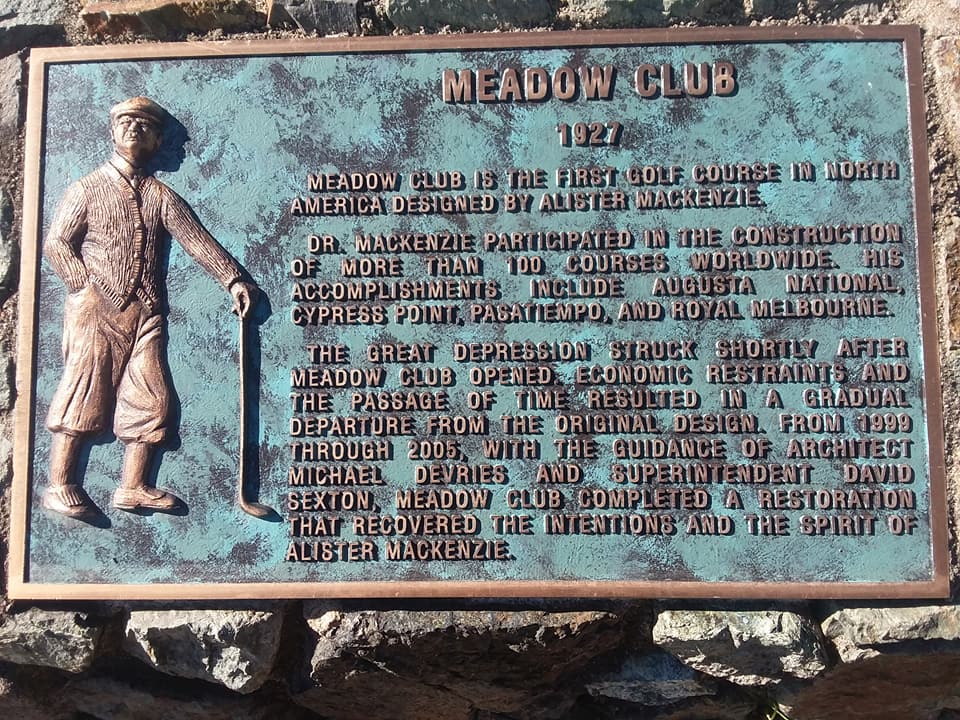

Although it’s Mackenzie and Hunter’s first North American collaboration, hardly anyone east of the Sierra Madre has heard of Meadow Club, much less been there, and I felt an intrepid explorer as we wound our way up the rocky highway, spiraling higher and higher, amid steep chasms yawning on either side, before finally arriving at the club gates.

Named for Bon Tempe Meadow, Mackenzie and Hunter’s design blends perfectly seamlessly with its setting, one of the most eminently natural courses in the world. Tie-ins between golf holes and the variegated flora of the high desert ecosystem are perfectly smooth. The course looks like it’s been there forever, exactly as nature intended, just with an assist from humans.

The kudos belong to Head Superintendent Sean Tully and his crackerjack team, because Meadow Club now looks and plays like it did almost 100 years ago. Long views across the property, fast, firm conditions, little to no rough (including a vast shared double fairway for both 13th and 15th holes reminiscent of St. Andrews’ Elysian Fields) and minimalist sustainability make it a textbook example of how to present and maintain a golf course in the 21st century. With the right kind of eyes, you’d think you were still playing on opening day 1927.

"Our course would look ridiculous striped out,” Tully snorts. “Not everything has to be green, and when you start with that understanding, good things happen."

Tully knows from personal experience. During his tenure, terrible drought conditions in California forced the club to use less water. Adapting on the fly, they kept the course just a little drier, just a hue lighter: not quite the “biscuit brown” you find in the UK, but also not PGA Tour green either.

Something wonderful happened: The members loved it.

In a move that should be echoed at every club in the nation, the members embraced it, welcomed it, celebrated it, and their patience and willingness to learn resulted in playable, fast and firm conditioning.

The course thrived.

“It’s not how it looks, it’s how it plays. What shade it is doesn’t matter,” concluded Tully.

It was a long, rugged road to get to this point, however. During the decades between its opening and the new millennium, the course, like so many Golden Age designs, declined architecturally and agronomically. From 1940-1999 needless bunkers were added by Harold Sampson, Robert Muir Graves and Forrest Richardson, as well as several greens committee chairs. Moreover, lazy mowing patterns changes playing angles of the golf course significantly away from the intended strategies of Mackenzie and Hunter. Greens shrunk, fairways narrowed, trees encroached and many bunkers looked out of place. Tully once humorously harrumphed that he thought they poured gravy on the course -- that’s how over-the-top it got.

But all that ended in 1999, when the club not only hired Tully as an assistant (a position he held eight years before ascending to Head Super), they also chose minimalist Mike DeVries over a gaggle of four other architects, including Rees Jones.

Tully, his team and DeVries set to work immediately, clearing 400-odd trees and opening up wide views across the property. Clearing all that space also allowed Meadow Club to be at the vanguard of a second great architectural and sustainability movement – less rough.

“By shaving the rough between fairways and around bunkers, not only will balls roll into bunkers more easily, but with wider fairways you get means more playing angles,” Tully noted.

Indeed, the bunkers are larger than their actual size since the land frequently funnels into them. The wider fairways may give you a shot at the green from the wrong side, but wicked green contours and greenside swales send off-line shots scurrying into places where up-and-down might be out of the question so you still need accurate drives to attack flagsticks.

The lack of rough also allowed them to interconnect fairways, much like Coore and Crenshaw did to such great effect when restoring Perry Maxwell’s last great design, Old Town Club in Winston-Salem, N.C. The best example occurs at one of the centerpieces of the club, the side-by-side par 5s, 13 and 15, sharing an enormous fairway, each hole peppered with bunkers and guarded by a side-winding arroyo drunkenly meandering its way between them. Goofy slices may end up in bunkers on the wrong hole.

“That’s the backbone of the inward nine. It’s got a St. Andrews feel much like the Elysian Fields, also on a par 5,” noted golf design expert Bruce Moulton. “It’s a highlight of any trip to play in NoCal and a masterstroke of both architectural strategy and minimalist maintenance.”

In between the two par 5s you’ll find, perhaps, the most charming of the four par 3s, the serene 14th with its green guarded by a pond. Indeed, while the routing showcases the par 5s in odd places – 1, 13 and 15 – the par 3s arrive more rhythmically – 5, 8, 11, 14 – every three holes.

“The fifth is our Eden hole,” notes Tully, pointing out the place where Mackenzie -- like Macdonald, Raynor and Banks -- would again nod to St. Andrews, with this version being much longer than the original. It is perhaps the longest Eden hole in America, stretching to over 200 yards from back tees.

Other highlights include the area near the halfway house, where several holes converge. The sixth and 15th greens are close together, along with their seventh and 16th tees. Set at the base of a fescue sovered rocky out-cropping, it’s a shockra of the golf course, a convergence of its metaphoric energies.

“Mackenzie liked routing courses so that several holes would converge around the most interesting natural features of the property,” Tully said.

Indeed, Mackenzie thought that the boldest features of the terrain resonated with golfers – those were the holes that were most exciting, hence you play into the teeth of the wildest natural features.

Meadow Club is reminiscent of Shanrgi-La, the famous Tibetan village in James Hilton novel "Lost Horizon," a place of restful beauty and a golf reverie from which a player will never want to leave. Lord knows I needed it. Logistics for the entire NoCal trip got thrown into chaos the night before my flight, so aspecial thank you for Meadow Club for being so accommodating. A place of restful beauty indeed.

With regards to my ground transport team, on the other hand: damn hippies! No one screws up a New Yorker’s groove like Californians. Whether it’s “DON’T REACH FOR MY VEGGIES WITH YOUR FORK THAT TOUCHED MEAT!” or “WHAT’S WRONG WITH YOU? YOU DON’T LIKE MY D.I.Y. ORGANIC KALE JUICE?” or “YOU CAN’T SMOKE THAT CIGAR OUTSIDE!” they can roach your buzz a grillion different ways, none of them good. Still, when they have golf courses this surreal, this idyllic, this heavenly, we can forgive them their idiosyncrasies. After all, a little California goes a long way.