SPRINGFIELD, N.J. – Right on cue, Baltusrol did what it always does at major golf championships -- surrender a record low score.

Sometimes it’s an immortal who does it -- Jack Nicklaus or Phil Mickelson, for example. And sometimes it’s a journeyman who comes out of nowhere; Lee Janzen or Thomas Bjorn leap to mind. Each of those four men set either an all-time in major championship single-round record, multiple-round record, overall scoring record (whether aggregate or score-to-par) or some combination of those three.

They were joined this week by…drum roll please…Robert Streb, as unlikely a person as you could have picked off he handicap sheet to go out and shoot a 63 in a major, but he did it yesterday in the second round of the 98th PGA Championship by carding eight birdies against one bogey (at No. 16) including a blistering 30 on the front nine. Both he and Jimmy Walker stand at 9-under 131 for the first two days.

By the way, that’s also tied for the record low score at a PGA Championship after 36 holes. In fact, had Walker not bogeyed the last, he’d have tied Martin Kaymer’s all-time major opening 36-hole record of 130 set at Pinehurst at the 2014 U.S. Open.

Stop the madness; this is getting ridiculous.

It’s one thing when players like Jack and Phil and Johnny Miller and Ray Floyd shoot 63, but we’ve seen three 63s in the last six major championship rounds. Phil Mickelson and Henrik Stenson shot bookend 63s at Royal Troon at the Open Championship just two weeks ago, and counting Hiroshi Iwata’s 63 at Whistling Straits last year, that’s now four times in one year and the last five major championships. In fact, we’ve seen, on average, one 63 per year in the majors since 2010. In the preceding 37 years it happened less than once every two years.

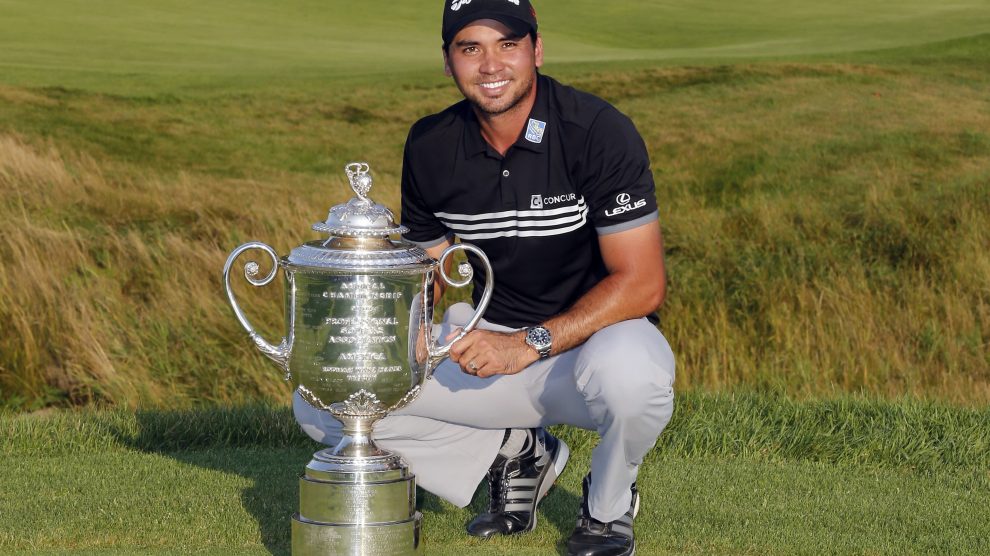

We’re also seeing 20 under par scores at majors -- and not at pushover golf courses. Whistling Straits, for example, is a difficult, dangerous, penalty-riddled layout, designed by no less a personage than Pete Dye, golf architecture’s proper rejoinder to a cross between Frankenstein, Godzilla and Sauron. But there’s Jason Day reakin every score-to-par record in majors and reaching the flabbergasting figure of 20-under. A thousand bunkers or not, no golf course can defend itself against the 420-yard drives that he, Bubba Watson and Dustin Johnson unleash with alarming frequency.

You may as well be trying to defend against Danaerys Targaryen’s dragons at that point.

Then there was Henrik Stenson, the human Iron Byron, closing this year’s Open Championship with a 63 to reach…wait for it…20 under. It’s not inconceivable that before this weekend is out, it could happen again. And it if doesn’t happen here, it could happen next year at Quail Hollow, the place where Rickie Fowler closed with a 62 to win the 2012 Wells Fargo Championship.

Even the U.S. Open hasn’t been immune to the onslaught. Rory rewrote the 36-, 54-, and 72-hole records in 2011 at Congressional, only to see some of them fall to Martin Kaymer at Pinehurst No. 2 in 2014. After the two bloodlettings we saw at Pinehurst in 1999 and 2005, it was unthinkable that Pinehurst would succumb like it did, but here was Kaymer, coming out of nowhere and trampling it underfoot.

There’s no escaping the problem: Records are like crumbling like the walls of Jericho. How do we stop this? Short of bringing back Tom Meeks and having him burn down Shinnecock Hills again for old time’s sake?

1. GOLDEN AGE ARCHITECTURE

Happily, some courses have proven impervious to the onslaught. Olympic Club, Oakmont, Winged Foot, Merion and Oakland Hills all continue to confound the players. Yes, Oakmont surrendered that 63 to Miller in 1973, but contrary to recent articles, he played Soakmont, a tempest-softened bastardized cousin of Oakmont that was more akin to a dart board than a golf course.

“That was a statistical outlier,” said golf architecture expert Bruce Moulton.

Other than Miller’s 63, since the advent of Tiger Woods, these courses have still proven as tough as tempered steel. The two U.S. Opens at Oakmont were won with 5-over 285 and 4-under 276 respectively. Oakland Hills was 3-under 277, while Merion was 1-over 281, and Winged Foot was 5-over 285. In fact, through their entire major championship history, here are the average scores for each golf course (using par-70 as a basis):

Merion +2.8

Oakland Hills +1.4

Oakmont +4.1

Olympic Club +0.6

Winged Foot +2.2

All of them average over par – and that includes an 11-under for Winged Foot at the rain soaked PGA Championship of 1997. Throw that out, and Winged Foot soars to 4.8 over par.

By the way, here’s a sure bar bet winner for you: How many water hazards are there combined on Winged Foot, Oly, Oakmont and Oakland Hills? Exactly two. (Five and 16 a Oakland Hills, for those of you scoring at home.)

So how do Oakmont, Oly, Oakland Hills, Winged Foot and Merion do it? How do they succeed in suppressing scoring while Congo, Medinah, Whistling Straits and Balty all get scorched? Movement in the earth: curvaceous greens, uneven lies in the fairway, reverse camber of the holes, diagonal angles of attack, elevation change and holes that dog-leg in awkward places. Golden Age architects often designed straight into the teeth of the fiercest natural features on the property.

Now architects bulldoze them in the name of “fairness.”

“It all starts with the greens,” explained Rees Jones, the quintessential golf course architect who came back just as his father did in the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘80s to prepare the course for a major. “Green contours have to be severe, and they have to run high on the Stimpmeter. Phil and Henrik were able to go low at Troon because those greens were running at 11 at the fastest all week. We have these running at 14, and before the rain hit, players were missing a lot of short putts. You need 13.5 at a minimum.”

Rees is dead solid perfect on that score. Flat greens are nothing but a green light to a pro golfer. Remember how Tiger Woods shot 63 at Southern Hills – even if it meant a slightly longer putt, he kept laser-beaming irons to the flat places on the green and taking his chances with slightly longer flat putts rather than shorter putts with considerably more break.

“I don’t like greens with elephants buried under them,” he famously said at Royal Liverpool, another place where flat greens triggered a record performance. But Oakmont, Winged Foot, Oakland Hills and Merion all have perhaps the most undulating greens in major championship golf.

“Golden Age golf courses have more contour,” agreed Golf Digest editor-in-chief Jaime Diaz. “Pete Dye courses are more susceptible because the greens are flatter,” he stated, and he’s right. Dye Courses have surrendered the following scores in majors: -8, -11, -20, -12, -13 – or an average of -12.8. On a par 72 course (all Dye’s major venues are par-72) or 277. Adjusting that to a par-70 scale, they average 3under.

That’s almost eight shots easier than their Golden Age counterparts.

Merion and Olympic Club have further natural defenses. Merion has exactly 18 flat lies on the golf course – one on every tee box. After that, the ball is above your feet, below your feet or side-hill every which way. That means golfers must factor in the spin such lies impart to the shot. Additionally, most of the short par 4s dogleg in awkward places. At 15, for example, you can run through the fairway out of bounds, like Sergio Garcia did twice, leading to a 10 and an 8 on what looks on the card to be a dinky little par 4.

Oly, on the other hand, uses reverse camber. Holes dogleg one way, but the land flows the other, putting a premium on both distance control and accuracy. That’s why methodical, meticulous shotmakers win there over long bombers. It’s a natural defense to scoring.

2. SETUP AND CONDITONING

Additionally, architects and pundits agree that setup and conditioning are having an enormous affect on scoring. Baltusrol is almost jokingly soft this week (thanks to the rain). For goodness sake, Patrick Reed embedded a ball in the green on Friday. I’ve played this game 43 years and covered the Tour for over a dozen, and I’ve never seen that ever before. Mark Kuhns, a magician of a superintendent with five major championships under his belt had this course in perfect shape with a month to go, but a month of rain and he bad luck of more during championship week is enough to de-claw any golf course.

“July and August are peak scoring conditions in the northeast. It rains, and it’s 95 degree, so the ball flies farther and it’s soft,” surmised golf architect Steve Smyers, who designs have hosted women’s majors and OGA Tour events. “Even with long rough, they can manage their way around. And then when the rain comes, conditions get easier still. That’s what you’re seeing out there. They should play in May or October, then you’d see how much more firm and fast the course would play.”

Troon had the same problem. Open Championship venues are supposed to be biscuit brown, with puffs of dust rising from every divot taken. But the Troon of two weeks ago was green as Atlanta Athletic Club.

“I thought about having tarps put over the greens when it rains, but where would we store 18 of them that size?” asked Rees Jones rhetorically. “The other thing is that when it gets wet and soft, it also makes fairways easier to hit; the ball doesn’t roll into the rough as much. Maybe we need to go back to 3-inch rough off the fairways. These intermediate cuts stop the ball from running into the deep rough, the bad stuff.”

“With the intermediate rough, emphasis on driving accuracy has decreased,” agreed Smyers.

Also, if you want to avoid 20 under, lower par from 72 to 70. There’s eight shots right there. Rees Jones, however does have a counter-argument.

“A true par 5 should be three shots,” he said. I don’t always agree with him – the short par 5s at Augusta National are among the most dramatic holes in golf, but if you want to avoid 20-under, that’s one way to do it. “Still, I don’t want the course to get too long. 8,000 yards is a shame. They should be able to keep scores down at 7,500.”

“They’ll shoot at least 16 under at all of my courses that have four par 5s,” said Pete Dye. “They’ll birdie every one of them.”

3. REIN IN THE EQUIPMENT

“It’s the equipment!” raged Pete Dye charmingly and laconically in a prior interview. “If they don’t do something about it, you’d have to bisect every fairway at the 300 yard mark with a ditch or something. Tell the USGA they have their heads in their keisters!”

Seriously, they banned the anchored stroke, but they don’t do anything about football helmets on a stick for drivers or catapults for irons. Let me switch hats and go back to being an intellectual property attorney for a moment. The USGA won’t limit the equipment because they don’t want to be sued by the equipment manufacturers. Well if the case ever came before Judge Flemma, the equipment manufacturers would set a record of their own…for swiftest judicial kick in the ass. Much like the music industry when they sued kids downloading music, the club makers are not a sympathetic plaintiff. No one is in a better position to create, advertise and distribute bifurcated equipment. So order the pros back to persimmon just like baseball players go back to ash when they turn pro.

4. USE BLOOD TESTING IN ANTI-DOPING PROGRAM

The pro Tours do not conduct blood testing for PEDs, only using urine samples.

“When you do that, you give cheaters a roadmap,” stated World Anti-Doping Agency committee member Gary Wadler, possibly the nation’s foremost authority on PEDs and sports, speaking specifically about golf in an interview the night Roger Clemens and Brian McNamee testified before Congress.

It worked like this: To get golf in the Olympics, the sport had to have Olympic standard testing of the athletes in place. So what the brass of the various tours did was to create the International Golf Foundation. That body would adopt the Olympic standard. However, the Tours themselves kept their far-more-lenient standards. Do you see the insidiousness of the arrangement?

“I could use HGH and get away with it,” stated Rory McIlroy in his Open Championship pre-tournament interview. “I was urine tested, not blood, on Friday of the U.S. Open; needs to happen in golf."

He added, “I think drug testing in golf is still quite behind compared to other sports.”

Here’s the inconvenient but critical truth: In the age of PEDs we have the mindset of “if it looks too good to be true, it probably is.” With records falling like leaves, that cynicism could potentially creep into the game as the sport lags behind in its drug-testing regimen. Players are using modern clubs that perform like old school clubs on steroids, but that we can see and hear.

Golf needs to figure out a way to find the Goldi-links: the right mix of architecture, setup and conditioning, equipment regulations and transparent, comprehensive drug testing that will ensure the world's best have to demonstrate a full breadth of skill to win on the biggest stages in the game.