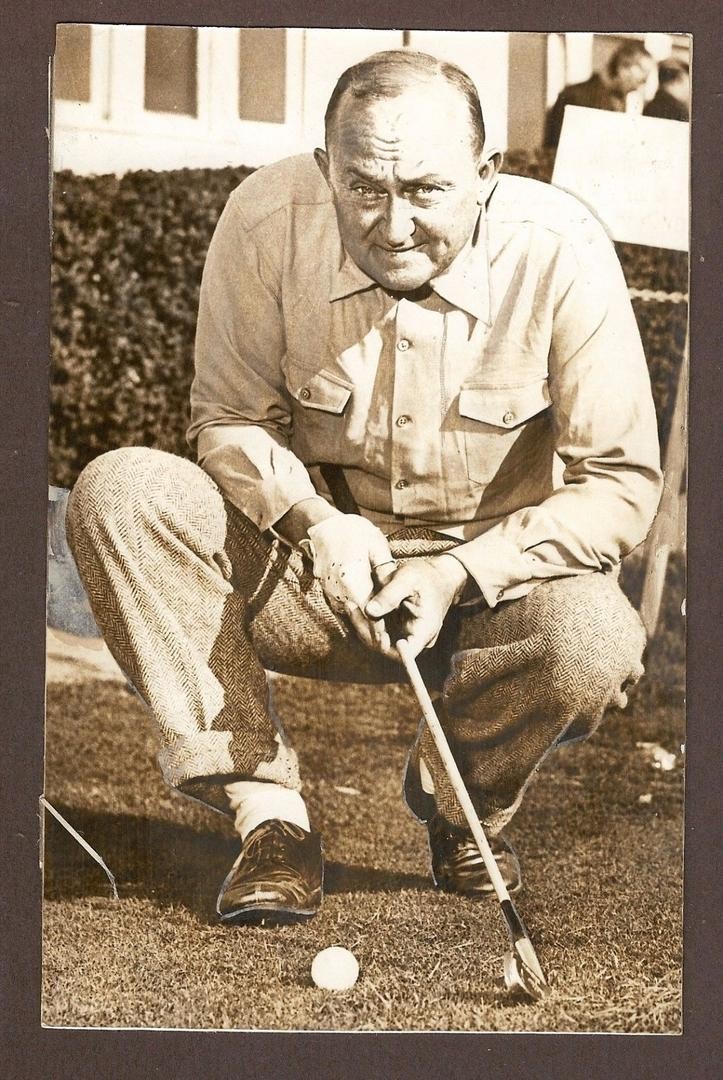

As a major league baseball star, Ty Cobb was the terror of opposing pitchers, both at the plate and on the bases. As an avid golfer in his retirement, Cobb acquired another notable reputation.

In 1948, Bill Cunningham of the Boston Herald, one of the highest-paid sportswriters of the day, told about Cobb having been a member of an exclusive golf club in California, most likely the Olympic Club in San Francisco. About Cobb and the club, Cunningham wrote that he “haunted the place and wanted to play every day, but his fellow members dived into holes when they saw him coming. He seemed to want to play mostly for the purposes of arguing. He liked to make a lot of small bets ‘just to make it interesting.’ Then he questioned every shot, every score and played every blow himself as if a World Series depended upon it. Very few of the brethren could take it. Golf wasn’t fun the way he played it.”

In a follow-up column after receiving a letter from Cobb, Cunningham paraphrased Cobb as denying that he was “an antagonistic sort of golfer.” Cunningham immediately added, “As I recall it, that ranking encyclopedia upon [sic] golf, golfers and golfing lore, Mr. Fred Corcoran [who became known in the sport as ‘Mr. Golf’], was my authority for that bit years ago” about Cobb’s golfing behavior. Corcoran, who was a co-founder of the LPGA, had arranged a three-city charity golf match between Cobb and Babe Ruth in 1941.

Months before that match, Cunningham wrote that Cobb “says these golfers miss the whole idea of competitive sport by chumming around together, eating together and even sympathizing with each other away from the course.” Cobb instead thinks that they ought to get mad at each other “and pour it on each other.”

“‘Why, if I were competing in one of these things,’ the old fire eater blazed, ‘do you think I’d even eat in the same dining room with the guy I was going to play? I wouldn’t even speak to him. I’d give him the absent treatment, even on the course, until I ran him nuts. That’s the way to beat somebody, get his goat!”’ That reporting by Cunningham plausibly led to the match with Ruth, because in the column, Cobb made the following offer: “I’ll meet him anywhere for any charity and I’ll pin his ears back.” Cunningham added, “In fact, Mr. Corcoran and I have wired Mr. Ruth just to obtain his reactions if any. Cobb says he’ll gladly come to Boston for the duel.”

Cobb would win the three-city match two rounds to one.

About his competitive instinct, Cobb uttered the following in 1957, at a time that he had given up golf for health reasons, to sports editor Art Rosenbaum of the San Francisco Chronicle: “I sure love to give the boys hell on the golf course.”

Upon Cobb’s death in 1961, Rosenbaum wrote that he played golf “almost as though the sticks were swords, to be thrust through an opponent if necessary.” He continued, “One day Cobb was surveying a 12-foot putt at the Olympic Club here. A biplane [a classic primitive-looking aircraft, with wings stacked one above the other] sailed noisily overhead and Cobb missed the putt. He was enraged. ‘You yellow blank swearword,’ he shouted into the skies. ‘If you had any guts you’d come down and fight like a man.’ Then he threw his putter high in the direction of the departing pilot. He also missed that shot.”

Rosenbaum also told the following Cobb golfing story from the late Frank J. Corr, an Olympic Club member. They played for $5, on the scale of around $100 in today’s dollars. “I won our match on the eighteenth green of the Lake course [of the Olympic Club] and the so-and-so threw the money down on the grass. A little wind came up and blew it into a sand trap. I took my time and walked after the swirling bill and finally picked it up, wiped off the sand, and placed it neatly into my wallet. All the time Ty was burning inside. I didn’t mind a bit stooping to pick up his money. The only satisfaction he would have gotten was if I had refused to bend down, or had fought with him about it.”

Fellow baseball Hall of Famer Tris Speaker, in a 1939 interview, recalled having played golf with Cobb during baseball seasons: “I used to go out with him now and then – and beat the pants off him – and the poor guy would be speechless if he dubbed a couple [missed some shots]. Finally, he gave it up and came out with the story that it was bad for ball players.”

In 1938, when The Olympic Club held its inaugural golf tournament, Cobb was one finalist. The other would go on to become a professional golfer and commentator: a then-12-year-old, Bob Rosburg.

In a video interview in 2007, Rosburg was asked about their pairing and said the following, with a few awkward transitions: “As I remember he was very nice to me. They said what a nasty man he was and everything like that, but he was fine to me. And I just annihilated him. I beat him 7 and 6. Of course I couldn’t go into the locker room. I was too young. They wouldn’t let me in.” Rosburg heard “they gave him such a bad time. All the other members, they thought that a 12-year-old kid beat a great legend like you – and they gave him such a bad time that he resigned from the club and didn’t play as a member there any more. He came back a couple of times to play as member-guest but he went down to Menlo [Park] and finished out playing down there.”

Asked about Cobb’s golf skill, Rosburg said, “Oh, he was a good player. Yeah, I would say, you know, he was an 8 or 9 handicap, something like that. Well I just had a good day and he had bad one.”

The golf great who Cobb was friendliest with was fellow Georgian Bobby Jones. In 1930, Jones would have one of the great years in the sport’s history, by winning what was then known as the Grand Slam. One day that April, Cobb was attending the Southeastern Amateur being held at the Augusta Country Club and, fortunately for posterity, hanging around the 16th hole.

Ahead of Jones were two groups of players “and the Jones party was forced to wait a good twenty minutes before it could continue,” the Associated Press reported. “Up to this point Jones was five under par and had only to negotiate the last three holes in standard figures for a new course record of 66. Bobby was tired and laid down on the grass. When the way was cleared, Jones drove, hooking his iron shot on the short par-3 16th into the woods. The ball laid behind trees, making it impossible for Bobby to play for the pin. He landed in a trap, chipped out, overran the cup and needed three putts to go down in 6 and ruin a great round.

“‘Did you see what that boy did?’ Cobb exclaimed. ‘He lay down on the grass, right when he was hot and keyed up. Why do they warm up a horse before they put him over the jumps? Why does a pitcher put on a sweater between innings? How can a man expect to hold his poise and his fitness when he lies down on the ground and rests 20 minutes?’ he asked.”

Sports editor Paul Gallico of the New York Daily News, after playing golf with Cobb in 1932, wrote, “My ball had a handicap stroke on the last hole of a nip and tuck [back-and-forth] match. He beefed all the way up the eighteenth fairway.”

During his career on the diamond, Cobb was known for his insightful analysis and unusual ways of preparing for the upcoming season. Some of his beliefs and practices made good impressions on top golfers. In his 1949 book "The Golf Clinic," Gene Sarazen wrote, “One day I was talking to Ty Cobb and asked him how he trained for running bases. He told me that he had a pair of shoes with lead in the soles and he used those to run around the bases in practice. Then when the game started, he would slip into his regular shoes and would feel considerably lighter on his feet.” Sarazen told of being inspired by Cobb to devise a golf club with extra weight, to strengthen the hands.

On a different front, in the Saturday Evening Post in 1941, Sarazen said Cobb had made the following point to him in Augusta: “Slumps in both sports are born of the same thing – too much tension. And the only way to get out of them is to relax and forget about it.”

In 1944, as accurately recalled in 1946 by syndicated columnist Tommy Hart, Byron Nelson had credited Cobb with providing him the following tip: “The Georgia Peach once told Lord Byron he shook off batting slumps by bunting.” Hart added, “Now when Nelson starts slicing, or hooking, he shortens his backswing.” In a golf articles series in 1949, Ben Hogan quoted Cobb in a different respect. Hogan and Cobb, back in 1940, had teamed for the first round of the Bing Crosby Pro-Am.

In a series of golf articles in 1949, Hogan would quote Cobb as having said that in baseball, “One of the chief faults in hitting is over-eagerness or over-anxiety. This makes you throw your weight too soon. As you step into the ball your hands and body must be working together.” Cobb, Hogan wrote, experiences the same thing on the golf course, and Cobb’s knowledge of leverage and timing “makes him recognize the fault and correct it faster than an ordinary golfer would be able to do.”

In 1957, sports editor Al Warden of the Ogden Standard-Examiner in Utah would write that long ago, Cobb offered Hogan the following advice: “Take two scotch and waters before retiring [going to bed], and you’ll never crack up.”

Cobb was a lefty golfer, and as of 1942, he was president of new group called the Northern California Lefthanded Golfers Association. A year earlier, he appeared in Bing Crosby’s movie short “Swing With Bing.” The tournament took place at the Rancho Santa Fe course in Del Mar.

Among the nicer stories of Cobb on a course is from San Francisco Chronicle sports editor Rosenbaum, upon Cobb’s death: “There was another side to Ty Cobb. One summer day, he had a little-boy caddie who had trouble packing Ty’s big golf bag. During the last nine Ty would hit his ball, then pick up the bag AND the boy and carry both to the next shot.”

Two of Cobb’s closest friends in the journalism profession were Grantland Rice, well known for his baseball and golf writing, and Russell J. “Russ” Newland. Newland, who is hardly recognizable today, was both the longtime president of the California Golf Writers Association, from the early 1930s into the 1950s, and the first president of the Golf Writers Association of America, starting in 1946. Newland was based in San Francisco during close to all of the 27 years in which Cobb’s principal residence was in nearby Atherton. Newland conducted some notable interviews with Cobb, and it is easy to speculate that they got along especially well. In a geographic coincidence, they each got to be first-hand observers in the 1930s to the launch of the baseball career of a native of San Francisco, Joe DiMaggio.