The golf downswing takes place in one-third of a second or less.

In that much time, the golfer must shift weight towards the target, rotate the torso, and drop the raised right side (right handed golfer) of the body down (side-bend towards the right). These actions start a cascade of movements which result in maximum acceleration of the club.

At the same time, the arms must straighten out at the right elbow and both wrists. The arms must also simultaneously deliver the club to the ball from “the inside” and not “over the top” – for suitable direction and trajectory. As the body and arms are all moving throughout the back- and down-swings, so too, is the head.

While the roles of the body and the arms are really quite different, the typical golf swing bundles them all together during the backswing. The most important body part that causes this “bundling up” is the right scapula, or shoulder blade. It has strong muscles that attach it to the trunk (which is why you will often hear the term “scapulothoracic joint”). At the same time, its position in space, at the top of the backswing will determine which direction the right arm starts the downswing from. The right scapula gets positioned to face the sky in a typical backswing, as the left side of the body – shoulder, trunk, hip and knee side-bend and face downwards. If, in the downswing, torso rotation happens before the right scapula can face downwards, the swing becomes an “over-the-top” one. The scapula, then, is what makes the body and the arms closely interconnected.

Incidentally, the small time-frame of the downswing includes the time taken for the message to be passed from the brain to muscle (“nerve conduction velocity”) and the time between the message reaching the muscle and its beginning to contract to move a joint (“electromechanical delay”). Then there is the fact that the typical golf swing moves several joints - the head (cervical spine), the thorax (central spine), the pelvis, the hips, the knees, the ankles, the shoulders, the elbows, the forearms and the wrists. How does the brain control all this movement, do it well and do it within a third of a second?

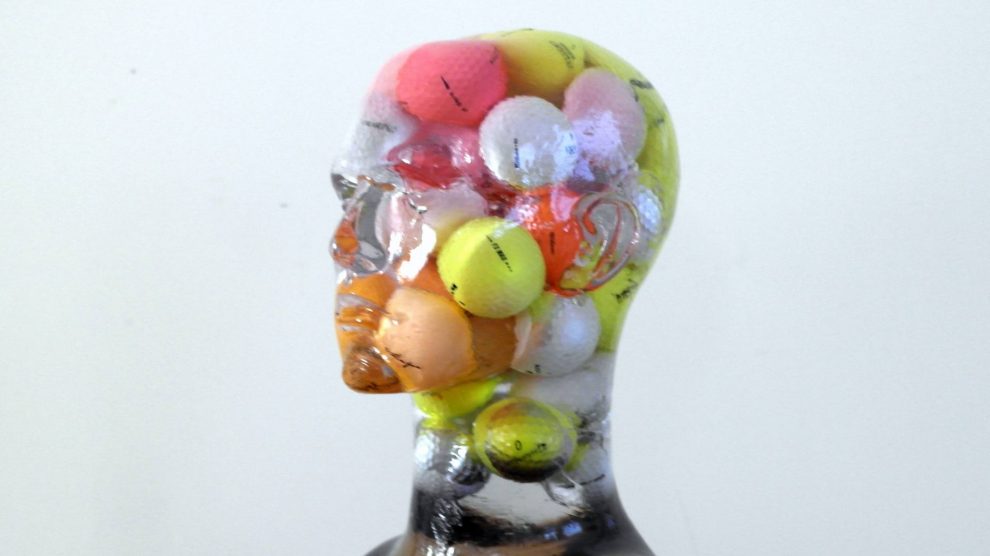

First a basic description of the brain, its structures and function, is in order. The brain, and with it the spinal cord that runs through the spine, together form the “central nervous system” (CNS) and consist simply of nerves. A nerve is a special type of cell, designed for the specific purpose of propagating electrical impulses to and from various body parts. Each nerve is much like a balloon on a long string in its design. The “balloon” is the cell-body where actual life-processes take place, and the “string” is the axon of the nerve that conducts electrical impulses received by its cell body, to neighboring cells. In all sections of the brain and spinal cord, the areas that contain cell bodies are termed “gray matter” and the areas that mainly consist of the axons of nerves are termed the “white matter”.

The brain proper consists of three major sections – the cerebral cortex (cerebrum), the cerebellum and the brain stem, and these are the main areas that “mastermind movement”, while the spinal cord’s role is largely to “pass on the message” and deal with simple, mostly unconscious, reflex activity. The cerebral cortex is the main part of the brain, lies under the skull, and has many complex infoldings in it. The cerebellum has an even more intricate series of peaks and troughs on its surface, and lies in the back of the head. The brainstem has many roles including to connect the upper parts of the brain to the spinal cord. Finally, the spinal cord consists of nerve axons travelling down the spine which pass on impulses to the “peripheral” nerves which then activate the muscles of the trunk, the upper limbs and the lower limbs.

The cerebral cortex (especially the front part of it, the frontal lobe) is the “boss” and makes an executive decision such as “I want to move”. It “asks” its “right-hand-man”, the cerebellum, which is the coordinator of learned movements, to “pull up a suitable template” for a desired movement. It can, however, at any time, make an executive decision to allow or prevent a precise template from being activated. As movement commences, the small organs in the inner ear detect head motion, and a message is simultaneously passed to the muscles controlling the head, neck, trunk and eyeballs, so that they can all be coordinated and synchronized to maintain balance.

Not only do each of the three main parts of the brain have specific roles, but within those roles there is “somatotopy” of which parts of the body each subsection of the brain will manage. The cerebrum (cerebral cortex) has a large part of its motor (movement) department allocated to the movements of the head, face and upper limbs. The trunk and legs have relatively fewer parts of the brain responsible for their movement. The deep gray matter that lies in the heart of the cerebral cortex – the basal ganglia – are said to guide the positioning of the trunk to better facilitate the movement of the limbs.

Similarly, within the cerebellum, the central part coordinates the movement of the trunk, while the outer (more lateral) parts supervise the upper and lower limbs. Even within the brainstem and the skinny spinal cord, the regions that carry messages to and from the trunk and pelvis and those that transport impulses to the limbs are separated.

Finally, there are even different arteries supplying blood to the different parts of the brain that “subserve” the upper body and face, and those that control the lower body. In other words the entire brain and spinal cord are designed with a specific pattern in mind - to have clearly delineated areas for the control of the “extremities” (limbs) and for the trunk/torso. Of course, in golf the main limbs of concern are the arms, as the legs remain fairly quiescent throughout the swing.